The Diary of a Nose

Book Review

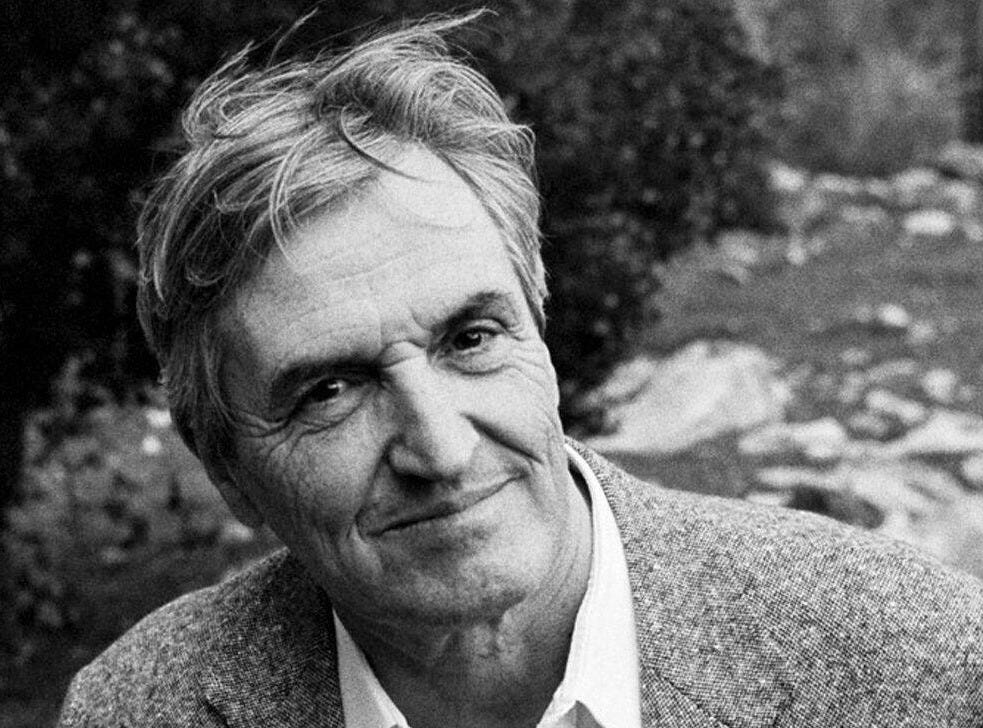

In short entries that are sometimes factual, sometimes impressionistic, Jean-Claude Ellena talks about the world of perfume that consumes his life and work.

Aged sixteen he embarked on a career in perfumery ‘as if it was a religion’. The company he joined was based in an ex Capuchin monastery.

These days, working in a hilltop eyrie on the Côte d’Azur, alone but for an assistant who weighs out the formulas and makes the coffee, he paints a picture of himself as an anchorite, serving at the altar of scent.

The solitaire reveals himself as the diary unfolds. He talks about his struggle to compose — sleepless nights, the animal need to ‘tackle each creation with a pared down response’. His application to his art is almost eremitical.

~~~

The book is wide ranging and eclectic. Foreign travel, business meetings, molecules, food, wine — everything that affects the process of making a perfume is ripe for comment. It’s all handled with the same light touch that he aims to give his creations.

‘We reveal a part of ourselves when we compose a perfume’ he writes, and in this sense, writing a perfume is no different to him than writing a diary. He is consciously addressing an audience, and the diary is the soap box where Ellena has his say.

And he has plenty to say.

He says that until the 1970’s, apprentices had to be familiar with around forty archetypes of perfume. ‘These rules, standards and aesthetic canons [meant that] perfumers were in possession of a repository of knowledge akin to an inheritance, a tradition and a national identity.’

But since then, perfumers have no longer had ‘to comply with standards dictated by bourgeois aesthetics and nineteenth century budgets’ — which would seem to be a good thing, but the result of this freedom is a perfumery that ‘trumpets its pleasantness [and] boasts about its performance’.

The only real innovations of the 1980’s -he writes- were not artistic but technical, the use of new products and headspace technology.

As well technical changes, the main impact on perfumery is how it’s been re-organised. In the hands of multinational corporations, the industry has changed its stance from ‘having something to offer, to one that responded to demand’ — something mainly due to the triumph of market research.

Ellena clearly feels aggrieved that perfumers have been relegated to the status of hired guns, there to carry out the marketer’s blueprints, which often contain nothing but the distillations of panel tests — which themselves reflect nothing but the public’s taste in perfumery, a taste that is largely driven by what they already know. This approach sets the bar to the lowest common denominator, resulting in rapid output of flankers and snail’s pace innovation. This is something Ellena resists. His work has long been informed by his artistic vision. For much of his career he was like a Michelangelo, told by Hermès to paint that ceiling and left to get on with it.

For all his criticism, there are no angry tirades in the diary, instead -he says- he aims for ‘a serene presence’.

Being an established Master, Ellena can’t resist the teacher in him, and he gives some advice to the young perfumer — ‘a dark harmony of spearmint and patchouli is more suited to an Eau de Toilette than a cologne, which should be more vivacious and afford instant pleasure’.

And again — ‘traces of violet leaf absolute combined with a high dose of Iso E Super reveal the peppery aspect of this molecule’ [Un Jardin sur le Toit].

‘PEA, once used to evoke the smell of roses, can also be used to create the smell of sake or cooked rice.’

‘Edible smells are lazy; something appetizing is exiting.’

On a higher level, Ellena wrote that in the 2010’s perfume was ‘moving away from references to nature’, and composition was no longer about adding different accords but ‘creating a vision of a whole’. He advised his contemporaries that ‘haute parfumerie should develop a new style of writing, redefine quality and find a new form of expression’ — possibly a reference to the indie scene that was developing at the time.

Seeing as the cream of the niche world was being gobbled up by multinationals, these were timely observations : Jo Malone, Le Labo, Frédéric Malle, By Killian, L’artisan parfumeur, Atelier Cologne, Maison Francis Kurkdjian — all were being acquired by corporations that wanted to renew their offer; because, as the British health service knows, it’s easier to buy in talent than nurture it yourself.

From multinational corporations, Ellena turned his attention to the other end the industry — the bloggers, who are ‘both perfume’s biggest fans and its loudest critics’. Ellena says he envies and admires ‘the emotion and enthusiasm they show when they smell a perfume for the first time’ but he is also critical of them. Some bloggers treat perfume as ‘an emanation of fashion’, and there are those who ‘create the conditions for an addiction to perfume’. Despite that, he sees them as a kind of oracle, saying that he ‘doesn’t consult the stars but readily turns to the nebulous blogosphere’.

~~~

Instead of being a perfume priest -as he first appeared to be in the opening pages of the book- he is more of a Martin Luther, a rebel who attacks the institution he loves in order to reform it. Ellena’s is a weighty critical voice, precisely because -like Luther- he’s deeply versed in tradition, something he received from his mentor Edmond Roudnitska, the great expressionist perfumer and philosopher of the art’s underpinnings.

Ellena is also a philosopher, despite having left school with no qualifications. In the diary, he brings insight to many subjects; his works in progress [Eau de gentiane blanche, Voyage d’Hermès - which he was in the process of changing from an Edt to an EdP] and more generally, he talks about the trials and errors on the way from first idea to finished perfume.

He tires to define his art —

‘Cézanne’s watercolours contain areas of wash that don’t overlap. I proceed in a similar fashion’.

He says what he thinks perfume should be, and what it is —

‘perfume doesn’t need a subject, a concept; it’s beautiful if it exists in itself.’

He even deals with the notion of time —

‘I am wary of nostalgia; it confers on perfumes a complacent seductiveness.

I cannot predict the future, and those who try often get it wrong.

In fact, I am not aiming to be side-lined, but outside [of] fashions, trends and time — and yet [still] of the present.’

He sums up his approach like this —

‘When smell is no longer linked to memory, when it no longer evokes flowers or fruits, when it is stripped of all feeling and affect – then it becomes material for a perfume.’

~~~

On the front of the hardback, Lucia van der Post compares Ellena to Mozart. A more accurate metaphor would be to call him an olfactory conjurer. He might wave two blotters in the air and make chocolate or white lilac appear under your nose (which he does in the book) but these are just party tricks.

The real magic is in the perfumes, which evoke watercolor visions that can’t be captured in words.

Journal d’un parfumeur (2011) by Jean-Claude Ellena can be found at archive dot com

The English version, Diary of a Nose (2012) is published by Penguin

I love his work through and through! And this little book is a fantastic light read for anyone who doesn’t feel that perfumery is a heavy art form but one that is about pleasure and hedonism.

I have studied some of his compositions and should revisit Poivre Samarcande on my own Substack soon. BTW the violet absolute quote with Iso-e-super was not about Sur Le Toit but Poivre Samarcande - hence the peppery connection.

i admire him so much!