A white haired gent in dark suit and cane, when Michael Edwards met the president of the Osmothèque Patricia de Nicolaï, he bowed and kissed her hand.

He came to give a talk about his new book — American Legends: The Evolution of American Fragrances, a companion volume to Perfume Legends, which dealt with French fragrances.

This new book was a long time in the making Edwards said. Perfume Legends was updated in 2019 and since then he had been planning a sequel but had been overwhelmed by the constant avalanche of new releases, which he and his team catalogue for the database on his website fragrancesoftheworld.com

Edwards described how his technique of analyzing perfume evolved from his work in the industry. In his role as marketer he would attend meetings to discuss perfumes in development and the team would give him fresh smelling strips. ‘That’s fine for the head notes’ he said, ‘and that’s what sells a perfume, but what drives repeat sales is the body and the drydown’. And so he started asking for drydowns as well as departures, which became the core of his work as a perfume taxonomist — as he describes himself. Perfumes are classified by their base notes, which form the underlying core of the structure and hence determine its character. The top notes that hit you right out of the bottle are like meeting someone for the first time and encountering their persona. The body of the perfume is their self, which only appears later when you’ve got to know them.

It was Covid that gave him time to work on his long delayed project. He was in paris, he says, and caught the last plane to Australia, which then closed its borders for three years, giving him time to work up the interviews, research and data that had built up over the years. He finally had the time and space to work it into book form.

In a recorded video introduction, Luca Turin described how Edwards is always polite but very persistent with his interviewees. His voice a harmony of highs — which swoop down to middle lows and then back up to highs at the end, Michael will ask his question again and again, until he gets the answer he’s looking for.

Thanks to this doggedness and persistence, his work in documenting perfume is an important step towards recognising perfumery as an art form; because -as Turin pointed out- no art can be taken seriously without a proper history, and history is based on documentary evidence.

Edwards’ charm and determination must have served him well in a field that can be as ruthless as the fashion business.

He is also lucky.

He recalls how he was account executive for the Halston perfumes at Revlon.

The development process was long and difficult. Halston had a hands-on approach and would take an interest in every detail, including the bottle shape of his eponymous feminine – which was expensive to produce because it needed custom machinery to make its unusual bent form.

The perfume though, when finally released, paid handsomely. After two years it was selling more than the rest of Revlon’s perfumes put together.

Another huge success was Passion – Elizabeth Taylor, the first celebrity perfume. Edwards was in Dallas the day of the launch and he remembers the mayhem when 10,000 people descended on Nieman Marcus trying to get a bottle before the stock ran out.

These are great, and not-so-great perfumes respectively, and this is part of Edward’s approach to his subject. He didn’t just choose the best -and best selling- perfume from the states; there is a broader vision than one based on sales figures. He chose every perfume, great or small, because it shows some important trend or development in the history of American perfumery; from the first perfume made on American soil — by William Hunter, a Scottish perfumer who opened a pharmacy on Rhode Island in 1752 — to the first big niche perfume made in New York.

A largely unknown work is Antonia’s Flowers, which has now disappeared but was the first perfume to employ headspace technology. Another unsuccessful but important perfume is New West for Her. It was the first scent to use an overdose of Calone — which became the keynote of the Aquatic genre. But — ‘there was too much Calone, people weren’t used to it, and they said it smelled harsh’. New West was too much too soon, and it flopped.

The industry has now taken the lesson on board and proceeds by the most hesitant of baby steps when developing a new scent — hence the prevalence of briefs saying ‘Give me something like X but not X’.

Giorgio was anything but a flop, but it had trouble getting off the ground. It was rejected by Estée Lauder and Helena Rubenstein before being accepted by Revlon, and they probably kicked themselves when they saw it flying off the shelves. But there are still those who would say they were right to turn it down. Giorgio wasn’t an easy sell – it was famously outlawed in restaurants. So, in response, Revlon gave away more than a hundred million samples in the biggest marketing campaign American perfumery had ever seen at the time.

Like Guerlain’s Mahora which sounds like Death to Rats in French, Calvin Klein could have run into difficulties — that is if the name ‘Climax’ had not already been taken. (Climax! - he said…) As it turned out they had no problem with Obsession — it sold by the truck load.

And, even in a country that is sometimes thought of as puritanical, sex still sells. Anne Gottlieb would say ‘If there’s no bosom, the fragrance isn’t going to be memorable’. It’s true that Eternity, one of the projects she worked on in the role of evaluator extraordinaire is a soft feminine floral — and being made by Sophia Grojsman you’d expect little else. But on the other hand, Anne Gottlieb’s massive hit cK One, which offered an a-sexual, clean-and-fresh perfume for both genders — that has no bosom at all.

Also by Grojsman, and also fresh and clean is White Linen, which, with its No5-like aldehydes and its rosy bouquet is not so original. But what is different about Grosjman’s debut are the two companions that went with it. White Linen was part of a trilogy of perfumes that were made to be mixed and matched. Along with Celadon and Pavilion it was the first example of a perfume designed for layering.

Another perfume that wasn’t that original, but completely changed the scene, was Brut. Brut was based on Canoë by Jean Carles, but made sweeter and given a ravishing base of musc ambrette, which turned out to be too expensive in the long run and wasn’t used for the follow up — Brut 33. The musks are also different in the new formulation of Brut which is still sold in Supermarkets; such is the lasting aura of Brut, the mark of a generation.

We were given samples to smell during Edwards’ talk, and he pointed out how similar Brut and Canoë are — and they really are. The likeness is so blatant -he said- because Karl Mann was given Carles’ original formula to work from, and he knocked in out in a couple of weeks.

Brut was a complete break from the previous generations of masculines : the sweet lavender of Pour un Homme de Caron, the spicy chypre of Aramis; Eau Sauvage.

The other reason for Brut’s enormous success in the seventies was a clever use of advertising. A famous footballer and a world champion boxer fronted the campaign in Britain, capturing the attention of dads and sons alike, and showing that it’s alright for men to wear perfume -and a sweetly soft one at that- without compromising their masculinity. Michael Edwards calls this trend the Playboy ethos (a soft porn magazine) which he says Brut seized on and made mainstream.

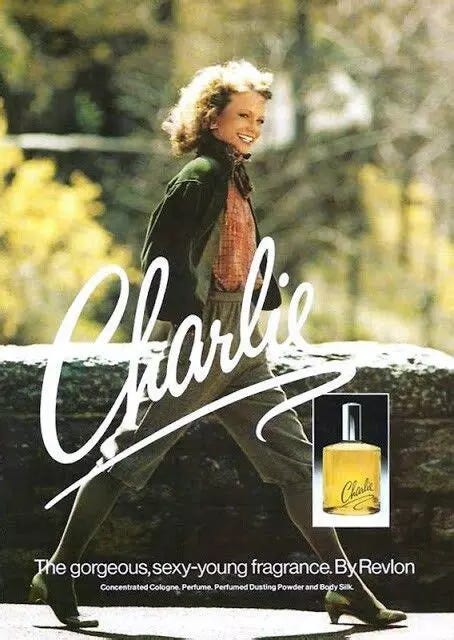

Charlie was released in 1973, five years after Brut, and it also brought about a change in behavior. ‘Before Charlie men bought perfume for women’ he said.

‘After Charlie women bought it for themselves’.

Where couturier scents had an elitist image, perfume was now becoming more democratic. A newly relaxed aura had settled over perfume in the seventies, which -in my opinion- led to one of the finest periods in perfume history.

Nothing stays the same though, and in 1991 the first Gulf War happened. People stopped flying — and stopped buying duty free. The market for perfume was devastated and the industry had to change tack; discounting became necessary for them to move their stock. The loss of revenue, and the loss of confidence that followed caused the main players to stagnate, which led to a new phenomenon, the rise of niche perfumeries — who didn’t share the ethos of Big Parfa and were prepared to experiment.

Niche had been around long before the nineties in the shape of companies like Jean-François Laporte’s L’Artisan Parfumeur, and Diptyque, but they did it for love — as well as the money. Eventually, niche caught on everywhere, not only in France.

In the seventies there were 70 niche perfumes. By the nineties there were 330 new releases, and in the 2010’s 10,600. There are only two niche perfumes in the book though; Dirt by Demeter Fragrance Library, a figurative ‘anti-perfume’ somewhat along the lines of works by CB I hate Perfume (by the same author) which have names like Burning Leaves and Rainstorm. Coming from a land where people can be so fastidious about ‘bugs’ and the like, calling a perfume Dirt is an ironic gesture indeed. The ‘real’ niche scent is Santal 33, Le Labo’s greatest hit, which was a viral success in the early days of social media.

Santal 33 (2011) is the last perfume in Edwards’ book, which -as well as talking about each perfume itself- looks at its background, and its bottle design as integral to the story. This global approach -sometimes lavishing more space on the development and packaging than the juice itself- gives the impression of treating perfume as a commodity; which is also one way to regard the book.

It is -no doubt- filled with fascinating facts and anecdotes, and is an absorbing read for those attached to the art, culture and history of perfume. But at 150 euros, or dollars, this is an expensive item — like the Fragrances of the World compendiums, which Edwards says were originally made for perfumers and retailers (who can offset the cost against their tax bill).

At around 40cm tall it would be difficult to fit American legends into many book cases, but it would sit nicely on a coffee table, which doesn’t quite do justice to the amount of time, energy and love that went into the making of it.

To finish I’ll let Michael Edwards have the last word: “for the French, perfume is liquid art, for the Italians liquid style, for Americans it’s liquid money”.

American Legends by Michael Edwards is currently available at the discount price of 12O €/$ or £108

~~~ ~~~ ~~~

Thanks for reading my article, which now appears on fragrancesoftheworld.com.

Good work. Interesting read. Thank you.

Shame his website & app are so appallingly clunky.

I have an d copy of his Perfumes from around 2017 bought heavily discounted. I don’t feel the need for either an update or this American Legends.

I’d rather spend on a bottle of something I love

Great overview. Despite the price, this book is still on my wishlist...